Last issue I introduced myself to you as NCHE’s new president. Prior to the presidency, I served as the education vice president, and my responsibilities were focused on the education and publications committee, which produces this publication and works to keep the website current. As president, my role is greatly expanded, and I am learning more and more about and am directly involved in the hard work that occurs under the leadership of the other vice presidents. For example, the conference committee is very active year-round. NCHE is embarking on our thirtieth year, and the 2014 conference will be the organization’s thirtieth. We just had a major meeting, and the plans are exciting. I personally am looking forward to one of our featured speakers, Dr. Anthony Bradley. I think you will find him to be inspiring and challenging.

A lot has happened in the practice of home education over the last thirty years, and the annual conference and book fair has always been NCHE’s main vehicle to serve North Carolinians. It brings to the state the best resources available, the most articulate speakers, quality curriculum developers and innovating peer educators: parents who were excited to lead workshops and share what they have learned about education in the home. Lately, I’ve had opportunity to hear stories of early NCHE conferences, see photos and even leaf through some of the early conference programs. Some of you have been there and can recall those early years. I, alas, was too young and in a far colder state. But I can imagine that it must have felt very different than our present-day conference, but at the same time, very similar.

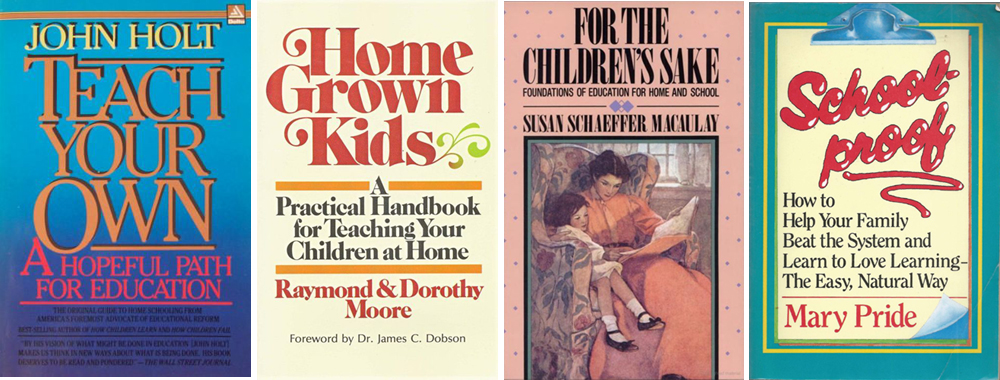

I am a student of the philosophy and history of education and, in particular, of home education. I enjoy reading the works of home education advocates from the beginning of the modern homeschool movement—the 1980s. Many of the authors, sadly, are no longer with us, or are no longer actively advocating. I wonder how many of you will recognize these names, some of whom NCHE was fortunate to have speak at the annual conference: John Holt, Raymond and Dorothy Moore, David and Micki Colfax, Samuel Blumenfeld, Susan Schaeffer Macaulay, Ruth Beechick, Mary Pride, Gregg Harris. These are just some of the names of influential home education advocates of the 1980s whose writings helped change the American education landscape. Not all these individuals advocated for home education in the same manner. Some, like Holt, were more oriented toward the philosophical, while others, like the Moores, were more empirical and focused on the research. The Colfaxes wrote from their homesteading experiences and were very practical. Blumenfeld was a historian who told the story of how public education developed. Regardless of their approach, however, each was an advocate for a better way to educate children. During the 1980s much of “the better way” was still being debated, even amongst themselves. So, even though these advocates did not see eye-to-eye on some matters, they shared insight into what facilitated learning (personal experiences), and where educating the next generation occurred (in the context of meaningful relationships, specifically in the home). Because of this commonality, they were unified in a hope for something better for the sake of our children. What they all had in common was a vision of healthy future generations, where people were passionate and actively learning, not just in childhood, but throughout life.

Some also went so far as to envision a society without schools. For Holt, best known for his concept of Unschooling, the process of instituting education portended an end to genuine learning. Schooling meant passivity and a squashed curiosity. Holt encouraged parents who guided, but he was suspicious of professional educators, and even of the notion of pedagogy, the science (or art) of teaching. Others were not so radical. One advocate, Mary Pride, in her book School-proof: How to Help Your Family Beat the System and Learn to Love Learning—The Easy, Natural Way (1988) envisioned a day when every town would have “Education Emporiums” instead of schools. She envisioned emporiums like in an antique mall with traders and booths full of their historic wares, where educators would offer their services, from lectures to laboratory experiments, and anyone could participate according to their own interests. In many ways, this is what the NCHE annual conference accomplishes, except its content is oriented toward a specific educational audience: home educators. However, Pride’s vision was more consumer-oriented. In some sense, Pride’s vision is accomplished by technology today. Not surprisingly, none of the early advocates foresaw the Internet (few futurists really did). No one imagined the significant changes the widespread availability of curated information and multimedia would produce. The World Wide Web, combined with powerful search tools, can help us locate the best answers to our questions. I am often amazed at the vast repositories of information, like Wikipedia, and sites with every DIY instructional video imaginable. But at the same time, the Internet has created a somewhat insular learning experience. For all its information and interactivity, the Internet and especially it’s newest incarnation, social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc.) raises serious questions about whether technology can truly stretch us, or simply take us to the places our patterns have predetermined, guiding us into increasingly smaller social enclaves which function to placate us with groupthink. I’ll be honest, as someone who has worked on the World Wide Web for almost twenty years (I made my first webpage in college in 1995), and who was enamored with the potential, and as someone who works in higher education and sees young people who have never been without the Internet, I have my doubts. I believe in “everything in moderation.” But even I get caught up sometimes in the number of “Likes” the latest NCHE Facebook post has received.

I started this column reflecting on the fact that NCHE is now thirty years old and that thirty years ago the leaders in home education advocacy were envisioning the future. We still need visions for the future, ones that carry forth the best hopes and ideas from previous visions but also hone them in response to today’s reality. Part of my role as president is to be the Chief Visionary for the organization. My own vision for our society is that we have, what I call, a “culture of learning.” I plan to expound on this vision over the next couple of issues, and it is my hope that I’ll get to talk about it during the thirtieth annual conference in May. But I wish to leave you with a foretaste. One of the chief characteristics of a culture of learning is the presence of, and active participation in, free, or voluntary, associations. In order for society to flourish, people must have the ability to mutually enter into and vacate social relationships. But they must have more than the freedom to do so. They must see the true value in organizing in order to accomplish mutually beneficial goals. Without a robust sector of free associations, societies collapse into power vacuums. A major worry about twenty-first century America is the diminished support of free association and over-reliance on either the State or the Market in order to meet needs. Both sectors have an important role to play, but that role is limited. They alone cannot sustain a vibrant civilization and a culture of learning. I believe their role, when it comes to education, is to partner with, and follow the lead of, the family and free associations. This partnership is important and warrants significant reflection, which I plan to provide in later issues.

For the moment, I am proud to say that NCHE is a free association. I, and my associates, voluntarily labor for our neighbors, the citizens of North Carolina, because we value education and believe it starts in the home. We work hard to build healthy relationships with state officials and law makers but also with curriculum developers. I want to see society flourish, and I want my children: Ransom (fourteen), Asher (twelve), Sigourney (ten), Toby (eight) and Corwin (eighteen months), as well as your children, to inherit a culture of learning. That vision is worth my time, talent and treasure.

Common Tags

Issues With Online Articles

- Fall 2022

- Graduate 2022

- Spring 2022

- Fall 2021

- Graduate 2021

- Spring 2021

- Fall 2020

- Spring 2020

- Fall 2019

- Graduate 2019

- Spring 2019

- Fall 2018

- Graduate 2018

- Spring 2018

- Fall 2017

- Graduate 2017

- Spring 2017

- Fall 2016

- Fall 2015

- Summer 2015

- Graduate 2015

- Spring 2015

- Winter 2015

- Fall 2014

- Summer 2014

- Graduate 2014

- Spring 2014

- Winter 2014

- Fall 2013

- Summer 2013

- Spring 2013

- Winter 2013

- Fall 2012

- May/June 2012

- Sept-Oct 2000

- Nov-Dec 1999